RNS for Epilepsy Has Long-Term Benefits

RNS for Epilepsy Has Long-Term Benefits

More than half of epilepsy patients treated with the recently approved responsive neurostimulation device (RNS) had reductions of 50% from baseline in seizure frequency lasting for up to 80 months, researchers reported here.

Among 250 participants in the pivotal trial of the implanted RNS System neurostimulator, approved last month for treating drug-resistant focal epilepsy, long-term follow-up indicated that responder rates increased steadily over the first 2 to 3 years after implant, reaching about 55%, said Martha Morrell, MD, chief medical officer of NeuroPace, based in Mountain View, Calif., which manufactures the device.

The responder rate was maintained out to 80 months in patients continuing that long in the trial’s open-label extension, she said at a press briefing held before her formal presentation at the American Epilepsy Society’s annual meeting. A total of 177 patients had at least 4 years of follow-up.

At the end of the trial’s blinded, randomized phase 3 months after implant, the mean reduction from baseline in seizure frequency with the device switched on was 37.9%, compared with 17.3% in patients receiving the device but with it turned off (P=0.012), which was the primary basis for the approval.

Morrell said that during the extension serious adverse events remained rare.

Sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) occurred at a rate of 4.7 per 1,000 patient-years of stimulation, she said. That compares with rates “in the mid-sixes” per 1,000 patient-years in recent studies of SUDEP in medically treated patients, Morrell said, and a rate of 9.3 per 1,000 in an older study of patients with drug-resistant seizures.

Rates of other adverse events were, with one exception, all less than 10%.

These included implant site infections, early battery failure, increased seizure frequencies, status epilepticus, and skin lacerations due to seizures. The exception was use of EEG monitoring, which was used in 16% of patients, presumably to investigate adverse neurological events of different kinds.

Most adverse events occurred in the first year post-implant, Morrell reported.

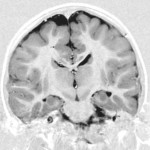

The device is about the size of a large man’s thumb, and is implanted and incorporated into the skull bone, she explained. It has two leads, allowing one or two foci to receive the stimulation.

Another important feature of the device is that it does not provide continual stimulation; rather, it monitors electrical electrical activity silently at the lead placement sites and delivers stimulation only when abnormal activity is detected.

During the entire follow-up period, 20% of patients were seizure-free for periods of 6 months or more. The median reduction in seizure frequency from 6 to 9 months after implant was about 30%, increasing to 39% at 12 months and 51% at 24 months.

RNS for Epilepsy Has Long-Term Benefits

Median reductions and responder rates from years 3 to 6 were both in the range of 55% to 60%.

Other epilepsy specialists told MedPage Today that the device appeared to be very promising for patients not responding to drug therapies and for whom definitive surgery is not an option.

Dawn Eliashev, MD, of the University of California Los Angeles, said her clinic already had a list of patients to be considered for the device.

“One of the things that was very frustrating for us, with many patients, is that we made extreme efforts to localize where the seizures were coming from in these very difficult patients, and the patients were faced with the aggravation that we found out that those areas were very close to language areas, or areas that were important for motor function,” she said.

That made them poor candidates for conventional surgery because of the risk of collateral damage and severe functional impairments. “Now we have something for these patients that can directly [target] those areas,” said Eliashev, who was not involved in the device’s clinical studies.

She emphasized that the device should not be regarded as an alternative to surgery. The latter “is a cure for epilepsy,” whereas the neurostimulator provides seizure reduction but seldom complete seizure freedom. Eliashev noted, for example, that most patients receiving the device still would not be eligible to drive.

One of the trial’s many site investigators, Jason Schwalb, MD, of Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital near Detroit, said the participants “were the sickest of the sick, that weren’t really candidates for standard resection.”

He also stressed limitations to the device’s efficacy. “You’re not going to see really huge cure rates. But for patients where there really aren’t other options, patients do get some benefit that’s clinically meaningful.”

Schwalb added that patients definitely seem to think the less-than-complete reduction in seizures is still beneficial for them. He cited a case in which a trial participant’s battery failed, and the patient demanded an immediate replacement.

“When the battery goes dead, it’s almost a surgical emergency” from the patients’ perspective, he said.

The RNS device has not yet entered commercial distribution — typical for complex medical devices shortly after FDA approval — but Morrell said it would begin shipping within a few weeks to selected epilepsy specialty centers.

She noted that the current FDA approval is for adult patients only. However, she said, the device would be able to fit into the skulls of most children older than 7- to 9-year-old, and NeuroPace is considering pediatric trials.